My internal community

I understand that the idea that we are a plurality of personalities does cause some anxiety for many people. For me it has been a revelation, and it is helping me to understand myself better.

I understand that the idea that we are a plurality of personalities does cause some anxiety for many people. For me it has been a revelation, and it is helping me to understand myself better.

In our society plurality is often understood as a disorder, a problem of mental health.

But as Meg-John Barker says in their free book “Plurality 1”: “An alternative approach to plurality can be found in the work of therapists and authors such as Hal and Sidra Stone, and Richard Schwartz, in the US, and Mick Cooper and John Rowan in the UK. They propose that we’re all plural rather than singular, and put forward therapeutic techniques for engaging with the different sides of ourselves such as voice dialogue: bringing different selves into conversation through talking - or journalling - between them. In such work the goal is not integration, or becoming a singular self, but rather improving communication between the different selves. The aim is that they can come to understand each other and work better as part of a team or constellation: rather as systemic therapy would work with a family system.”

“Both pathologising and affirmative approaches are united in seeing a key role of trauma in our experiences of plurality. The therapist-authors mentioned previously all suggest that plurality occurs because we disown parts of ourselves when we find that they are disapproved of – or punished by - the world around us. However, more affirmative approaches propose that this is something that we all do as a response to linked personal and/or cultural trauma. For example, parental messages and school bullying give children a clear sense of what is acceptable or not, often reproducing wider cultural messages about what is currently considered appropriate behaviour for someone of our gender, race or class. In this way we could usefully conceptualise everyone as operating under the conditions of intergenerational trauma - damaging cultural norms and ideals which are passed on from adults to children - which will likely have this kind of impact. Trauma-based understandings - located as they are in the body - also help to explain how plurality can be felt so viscerally with different bodies having quite different embodiments: posture, gait, speech, facial expression, and so on.”

“Indeed you could argue – as some sociologists have – that the concept of a singular self is an invention of neoliberal capitalism. We’re all pressured to tell stories of our self as if we were consistent and coherent when actually we’re all complex and contradictory. You could even go so far as to say that experiencing yourself as utterly singular is the ‘crazy’ thing, and that trying to present yourself in that way does quite a violence to yourself. Certainly many indigenous cultures have understandings of selfhood that encompass plurality and would see the idea of a singular self as weird or unlikely.”

In respect to the different parts of an internal community or of our plurality, there are different theories which I neither do not very well, nor does that matter to me. I like the way Meg-John Barker presents it in their zine “Plural Selves 2”, and I use that.

According to Meg-John Barker’s model, there are different roles for the selves, and each role can be played by more than one self. The roles they propose are:

-

Containers: they take care of the rest and have a facilitating role in the internal community, so that everyone works together well.

-

Cover-ups: Are often the selves we present to the outside world, the ones that have allowed us to survive in this world.

-

Carriers: Are the vulnerable parts that we pushed down and rejected, often they are extremely vulnerable and traumatised.

According to Meg-John Barker, the work that should be done with each role is very different, according to the role:

-

Cover-ups:

-

Should be allowed to let go of what they have been doing for so long.

-

Rest and being cared for.

-

Feeling ‘real’, as for so long they have been feeling fake, knowing that they are not the complete self.

-

Let them know that they did a good job getting us to where we are now.

-

-

Carriers:

-

Making themselves present, as the self they really are.

-

Feeling welcome and not like they would ruin everything.

-

Sharing all their pain openly.

-

Let them know how essential they are.

-

-

Containers:

-

Realise that they even exist.

-

Include them completely in your life/community/system.

-

Taking care of you instead of being delegated to look after others or being looked for in others.

-

My internal community is made up by my different selves. I am all of them together, and sometimes all these selves collaborate harmonically, at other times there are conflicts and chaos. And at other times there is one self that is very dominant, and the rest of the selves get backgrounded to a minor role, or even completely denied.

I probably don’t have completely clear yet which role each of my selves plays, and, maybe, some of them have changed their role, or do so sometimes. But I am still at the beginning of my dialogue with many of my selves.

I present: My Internal Community

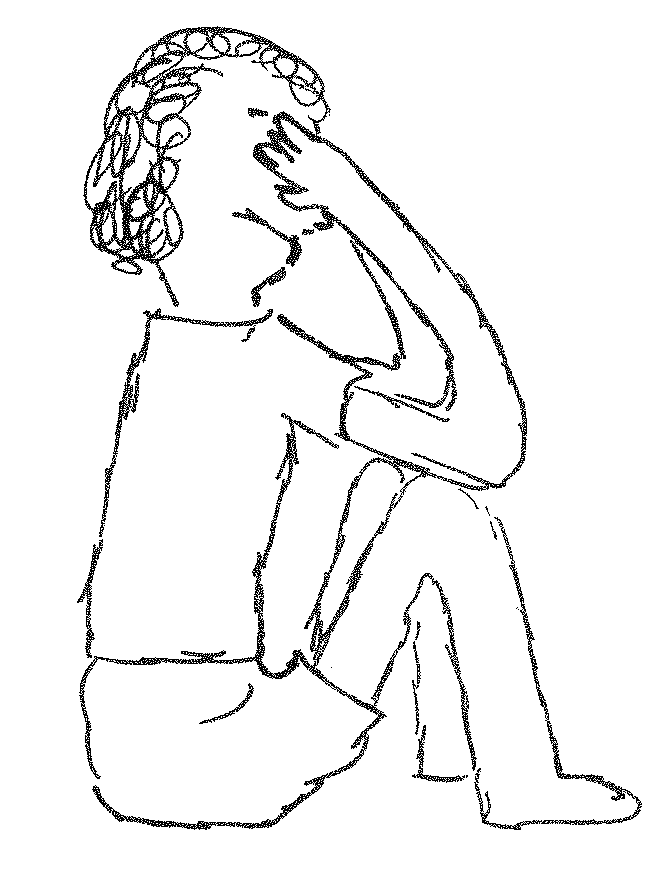

Zora

(or: my inner girl, 10-11 years)

Zora was the first, and I discovered her at the end of February 2022. At the beginning I didn't know if she was a boy, girl or nonbinary, and so as not to assign her the wrong gender identity I always called her my niñe (neutral in Spanish).

At first Zora wouldn't let me get close. She was very frightened, even of me, and sat in a corner, covering her eyes with her hands, on guard so that she could escape if necessary. Gradually she allowed me to come closer, and one day she allowed me to sit next to her, and put my arm around her shoulders. And she started crying and hugging me.

We've already come a long way together. Zora helped me to accept the sexual abuse she had suffered as a part of my life. It was she who told me one day that it had been my father.

Zora is very resilient. She has survived emotional neglect, sexual abuse, bullying, and more. She has become very strong, but at the same time she is very lonely, and still very vulnerable.

Over time Zora has become a fighter. She fights when it is necessary, and when she has suffered an injustice and, above all, when she feels ignored and unseen, she doesn't care if she hurts others in her struggle. In this sense, she can be brutal, even violent, towards others.

But Zora is also very empathetic, she has a big heart and cannot see others suffering. She has often intervened strongly when my inner boy - Alex - was suffering from violence or mistreatment.

she has a big heart and cannot see others suffering. She has often intervened strongly when my inner boy - Alex - was suffering from violence or mistreatment.

Zora got her name from the German TV series Zora the redhead, broadcasted in 1980: “Zora is the leader of a gang of orphans in a coastal town in Croatia. She is from Albania. She had left her country four years earlier to escape a vendetta that affected her family: during a hunt, her father accidentally killed a member of another family, who decided to take revenge by murdering all of them, men from Zora's family. Her uncle, father and older brothers were killed. She and her mother crossed the border from Albania to save the younger brother. Zora's mother died of the same disease as her younger brother, who only survived his mother's death for a few weeks. Zora did not want to stay in the orphanage; she is too freedom-loving for that. If she is the leader of the Uscoks, it is because she is the strongest.“

Although my Zora has her mother and father, she feels unseen, not understood, not loved - she feels like an orphan. And she has become strong and a fighter. But she is a single fighter. Zora has been invisible most of my life, partly by choice, as she was afraid to show herself openly. Even though I felt Zora as a child, we hid from out of fear. Now she needs to assert herself, also outwardly. It was Zora who pushed me to take oestrogen 4½ years ago, and it is Zora who now insists on my name as Andrea.

Zora identifies as a feminist and a lesbian. Beyond the men in my internal community, she has no interest in relationships with men or boys. Zora is still very lonely, and does not have her intimacy needs met.

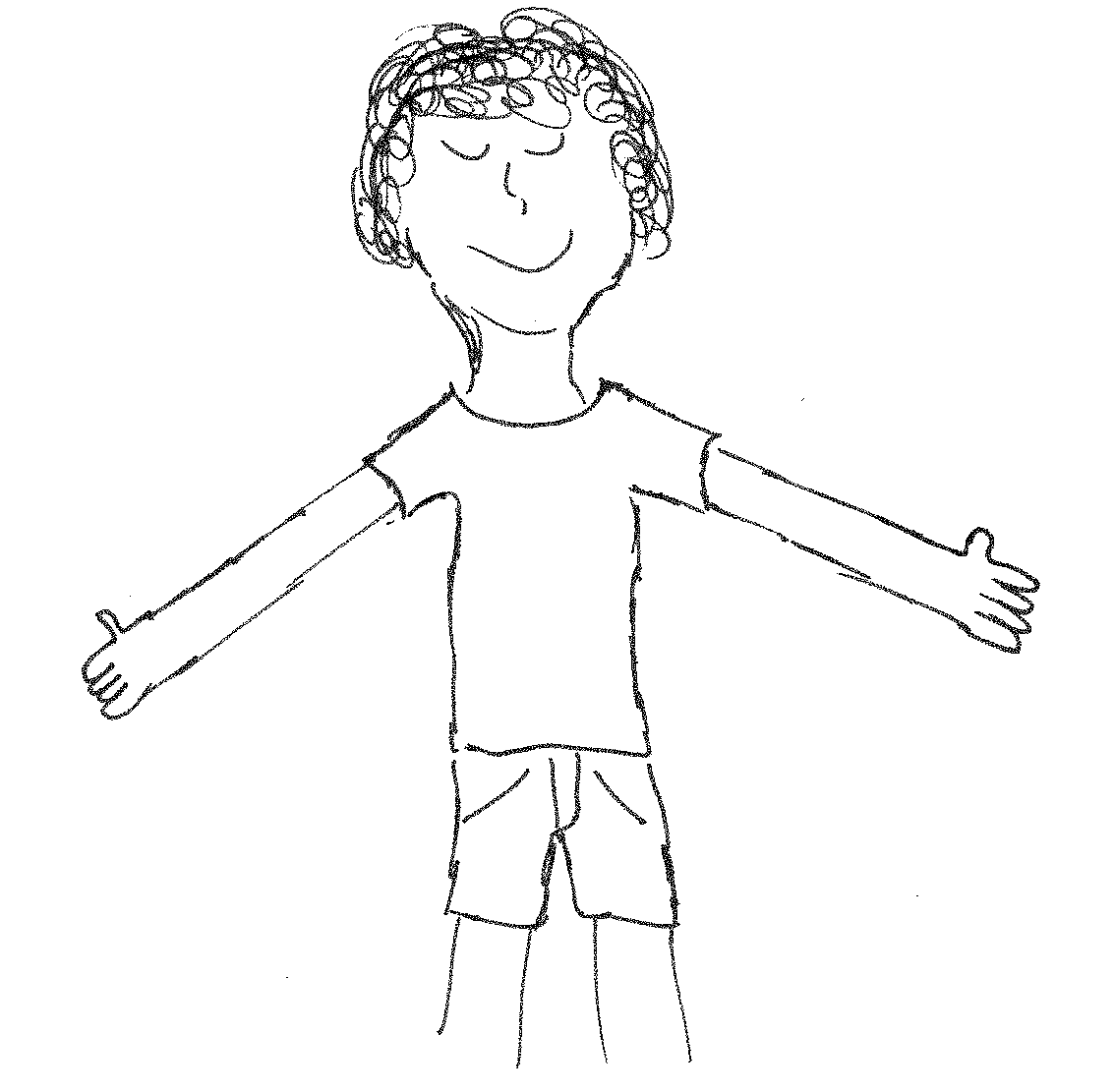

Alex

(or: my inner boy – 5/6 years)

Alex - my inner boy - only appeared at the beginning of December 2022. Initially I thought - as did Zora - that he was my parents' project of a boy, and the idea was to say goodbye to him (or, as Zora said, to kick him out of our house). But I soon realised that Alex is part of my internal community, and not my parents' project boy, and we took him in, Zora and me.

Alex - my inner boy - only appeared at the beginning of December 2022. Initially I thought - as did Zora - that he was my parents' project of a boy, and the idea was to say goodbye to him (or, as Zora said, to kick him out of our house). But I soon realised that Alex is part of my internal community, and not my parents' project boy, and we took him in, Zora and me.

At first Alex was very afraid of abandonment, he cried a lot when I hugged him and he clung to me. Eventually, he just hugged me, and little by little he started to feel safe "at home", and loved.

Alex was also very afraid of the night, or of my parents at night, which is still not very clear to me. He panicked at the thought of being naked on a table with a lot of fear of being touched. It seems that this table corresponds to a doctor's office, as he had his tonsils removed when he was a child. And it seems that he is no longer afraid of this table or doctor's office.

I still don't know how Alex will develop, now that he is not so afraid anymore. I still don't know what he likes to do. He is a very scared and shy boy, and not at all masculine .

.

Initially I called Alex "little Rigby", but in the end I don't know. Maybe Alex develops into Rigby, maybe not. The name Alex gives him his own identity, and gives him the opportunity to develop freely.

I call him Alex also as it is a neutral name - it can be short for Alejandro or Alejandra. Alex feels caught between the pressures of masculinity from his parents and other boys, and Zora's "I'm a girl!", and he doesn't really know what he is. He just knows he doesn't fit in. Outwardly he shows himself as a boy, with great difficulty, but I don't know how he feels inside.

Rigby

(or: my inner adolescent – 16-2x years)

Rigby is my inner teenager, between maybe 16 and 20 something. He is a very shy boy who has never felt seen, understood or loved. He is very lonely, has few friends, and between the ages of 14 and 16 has suffered homophobic bullying by his "friends". At this point, though, Rigby couldn't care less about discovering his sexuality, he had no idea how to identify himself. Most likely he was asexual, although this term did not exist in the 1980s. But he felt no sexual or romantic attraction to anyone.

Rigby flees the real world through books. He can lose himself in a novel for days, or stay up all night to finish it....

He doesn't care much about high school and then vocational training. He doesn't make any effort, and if a subject annoys him (like Latin), he simply ignores it and doesn't care about the consequences. But if something interests him, he can lose himself in the subject for days, weeks, or months.

Rigby is very weak, he feels a lot of despair about an unbearable life that he cannot change. He simply suffers in silence and escapes into his own world.

I think Zora was the one who took Rigby out of his parents' house when there was an opportunity to study in a city far away. It was good, though not enough to allow Rigby to become more confident.

Rigby's usual state is dissociation: not feeling, not feeling anything. Feeling is dangerous, as it could bring him into contact with pain, with suffering, with loneliness and despair. Better not to feel.

Rigby can spend hours making suicide plans in his mind. Impossible plans, and there's always some detail that doesn't work out. But - on the whole - he is not suicidal. Although, in times of crisis he may have suicidal urges.

The name Rigby comes from the protagonist of an autobiographical novel by Tom Spanbauer: Now is the hour. Although the context is very different from my Rigby, they both suffered the same loneliness, not feeling understood, not feeling loved. When I read the book during the lockdown - after several books on trauma it was the first novel I was able to read - I recognised myself in this Rigby, and I don't know how much I cried reading this book. So, my inner teenager is called Rigby.

Rigby only appeared a few days ago, and he has not yet gained confidence. He cries when I remind him that this is his home if he wants it. In general so far he doesn't let himself be touched (with one exception).

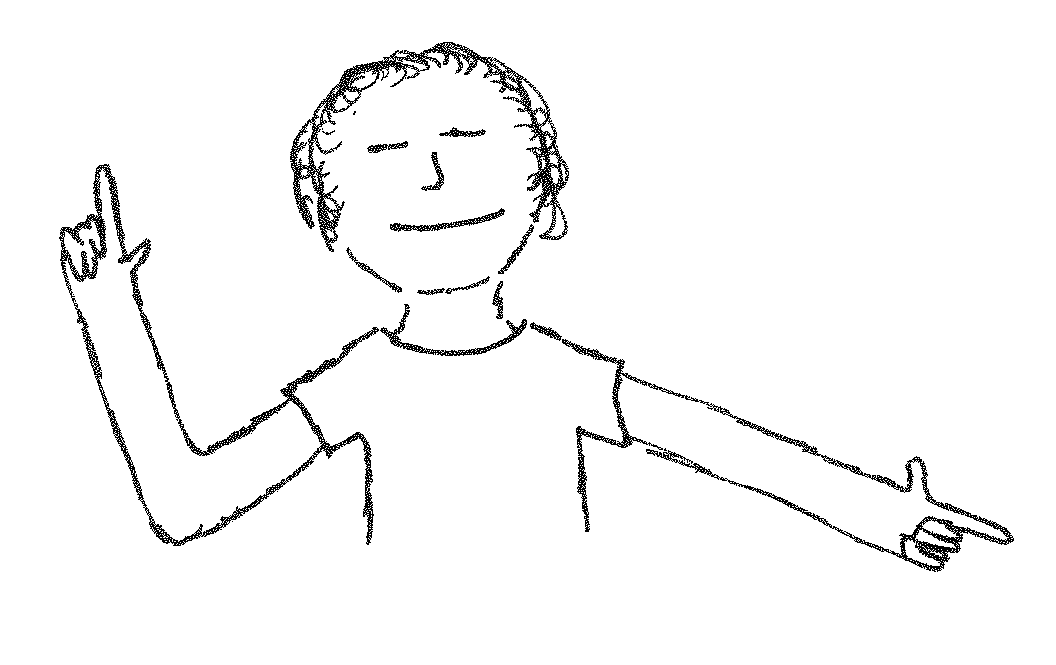

Cris

(or: the doer)

I became aware of Cris while reading Meg-John Barker's zine Plural Selves 2. In this zine Meg-John presents Max as one of their selves, and Max immediately reminded me of Cris. Cris was me until the pandemic, or, more correctly, he was the most visible me, the me that I showed outwards.

I think that Cris appeared little by little in my life during my studies and with the anti-nuclear activism (shortly after Chernobyl in 1986).

Cris is an activist, organiser, worker, and I don't know what else. Cris simply does, organises, etc, in order to get the approval of others (not of everyone - of a group that matters to him). At the same time, this way of Cris is also a way of escaping from herself, of not having time to stop and feel, not having to be intimate with other people. His way of relating is through activism and political debates, but he doesn't talk about what he feels (if he feels anything).

Cris works very well when Ginger gives him a vision. He works and demands even more of himself. At these times, my inner critic also has to remind him of the work for economic sustenance.

My Cris has no gender. Although the name comes from a specific person in activism from my past, my Cris has no gender. It is neither masculine nor feminine. That is to say, doing it all is not the macho activism of much of the left, but neither is it an activism that puts care at the centre, let alone self-care. Cris does. Full stop.

The pandemic stopped Cris, and he has never recovered since. He tried in the summer of 2021, attempting to return to climate justice activism, but to no avail. He had to withdraw again and went into a depression. He tried again in summer 2022, but at the Encuentro Sobremesa and - maybe even more, thinking about the trainings for a camp in Andalucia in October 2022 - he finally had to accept that he can't do it anymore, that he can't go back to his old way of doing it all. Actually he was already suffering from burnout before the pandemic. He thought he could do a Saturday training in Salamanca, take the night bus to Cadiz, and do another training in Cadiz. Once his body stopped him, and already at the bus station he cancelled a training, went home and went to bed. Burnout.

Now Cris has gone on a cycling trip around the world, to find himself. Nobody knows if or when Cris will be back, and what Cris will be like if he comes back.

My inner critique / my inner carer

I don't know if it's really the same person, as she's changed so much. When perhaps two years ago I did an exercise in Alex Iantaffi and Meg-John Barker's book Hell Yeah Self Care to draw the face of my inner critic, I drew my mother's face. However, I always saw my inner critic as male, but with my mother's face and voice. He was a very toxic critic, for him nothing was enough, he always told me "you can't do this, you never finish anything, you won't achieve anything, ...". The results of Cris' work were never good enough. Nothing satisfied him.

My inner critic was very demanding, always demanding more. He went into crisis with the pandemic, but tried to come back with his usual methods. I think that with Cris's escape - his journey - he finally understood that it doesn't work like that any more. There is no one who will respond to his threats and demands the way he wants. Zora would show him the finger (fuck you!), and Rigby would retreat even further into himself.

I think my inner critic has made a transition, even in terms of gender. I now see her more as an internal carer. It's not that she doesn't want us to do the things she thinks are necessary - like building us a new economy, for example. But she understands that by force things don't work, and that she has to respect the emotional needs of others, to take care of us so that we can get things done.

I still haven't found a name for my inner critic/inner carer. Or, perhaps, I need two names.

I think the rest of us now also see that this inner carer takes care of us, and that she is right that certain things need to be done. She encourages us, she supports us, she cares for us, but she doesn't threaten us. And because she does that now, we value her as a part of our community.

Ginger

Ginger is a person of visions. And, with her visions of a better world, of actions, etc. she has the ability to inspire others and motivate them. Or, also, the rest of the community, especially Cris.

In the past, Ginger's visions had more to do with a fairer world, with social struggles. With Cris's disappearance, and, perhaps, also realising that we also need a vision for our lives, Ginger's visions are now smaller, perhaps more private. Above all, she also thinks of her own community, the trans*, nonbinary and queer community, in order to construct visions.

Which does not mean that her visions are less transformative. But perhaps she has lost the vision of being able to change the world a little bit. Or, of being able to change everything.

When no one wants to listen to her visions, or the world is simply not for visions (the pandemic!), Ginger becomes depressed, shuts herself away and runs away from the world.

Ginger's name comes from the film Chicken Run by Aardman Animations. Ginger is the character who has the vision to escape from the chicken farm.

Andrea (?)

Andrea, although I don't know if it's really me. For the moment I give them my name. Andrea is probably my main container.

Andrea tries to make it easier for all the others to get along and cooperate with each other in a harmonious way. Perhaps they are also a very nurturing part, they give their love to the others when they need it - they have done it with Zora, with Alex, and now they are doing it with Rigby. Andrea makes sure that everyone feels at home, feels loved, seen and valued.

But Andrea also needs to feel loved, they also need the love of the others. Sometimes they feel overwhelmed and exhausted and don't know where to find the strength to make the others feel loved. They also need to be hugged, they need to feel accompanied when they have to cry. Who takes care of Andrea?