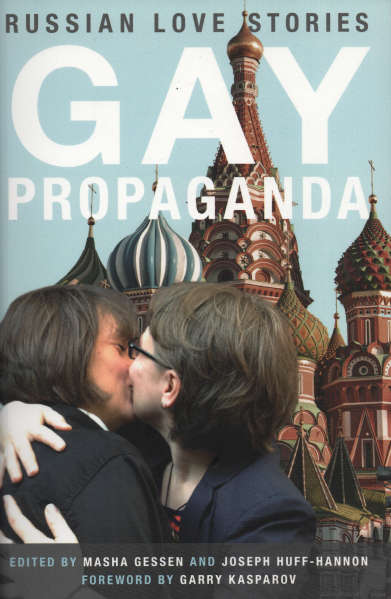

Book review: Gay propaganda. Russian Love Stories

Masha Gessen & Joseph Huff-Hannon (editors), OR Books, New York and London, 2014

Masha Gessen & Joseph Huff-Hannon (editors), OR Books, New York and London, 2014

ISBN 978-1-939293-35-0 (paperback), 978-1-939293-36-7 (e-book)

Russian and English, 224 pages

Publication of this book was rushed to coincide with the Sochi winter Olympics, and it shows. It shows, because – and the editors admit this – the spectrum of experiences is limited to mostly well-off Russian gays and lesbians, in their majority couples with the ability to travel abroad, and with higher education. The publication of the book is a response to a wave of state-sponsored homophobia in Russia, culminating in a bill banning “‘propaganda of non-traditional sexual relations” - often narrowly interpreted as banning propaganda of homosexuality, but in fact covering a much broader spectrum of non-patriarchal sexual relations (see ILGA Europe, 11 June 2013).

“Gay propaganda” brings together “Russian love stories” - stories of gays and lesbians (plus one trans*) - and their life in Russia, before and after the passing of the law. It is full of stories of the daily struggle against homophobia, of keeping sane in an insane environment, of hate and love. It is full of stories of how state-sponsored homophobia fuelling homophobic violence creates an atmosphere of fear and paranoia, and the power of people to overcome their fears and live their lives. But it also shows that homophobia does not reach everywhere – there are also mothers, fathers, and friends who have little problems with their lgbt offspring or friends, creating islands of sanity in a sea of homophobia.

Who is this book for? As Masha Gessen writes in her part of the introduction: “[T]his would be a samizdat project, the telling of stories for a small audience that needed it”. And this audience are lgbt people all the world over – but most likely in the countries of the former Soviet Union – that live in an environment of state-sponsored homophobia trying to keep sane. Here, the book can provide hope through the sharing of stories and experiences.

However, I still have some issues with the book, which lead me back to its limitations. The book focuses on gay (and lesbian) lives and identities, extrapolating from lgbt identity politics as we know it in the West. These get increasing challenged by queer activists, who question the normalisation of lgbt identities, and their universal applicability to a broader range of “non-traditional sexual relations” or gender identities. Little of this is visible in the book. Where are the Russian queers, trans*, or other sexual outcasts? Where are the men-who-have-sex-with-men or women-who-have-sex-with-women who do not identify according to Western lgbt identities, or who do not want to live a life based on heterosexual models of coupledom? Given these limitations, to me the title of the book – gay propaganda – takes on a second, probably unintended, meaning: propaganda for the normalisation of gay (and lesbian) identities along heterosexual models.

Andreas Speck