English

English Español

Español

Conscientious Objection - The Impact of International Mechanisms in Local Cases: the example of Colombia

Alba Milena Romero Sanabria is a political scientist at the National University of Colombia. She has worked for the recognition of the right to conscientious objection to military service for ten years, alongside participating in nonviolence training processes. She is a member of Asociación Acción Colectiva de Objetores y Objetoras de Conciencia (ACOOC, Conscientious Objectors' Collective Action) and Conscience and Peace Tax International. Her co-author Andreas Speck is originally from Germany, were he refused military and substitute service in the 1980s. He has been involved in the environmental, anti-nuclear and antimilitarist movements ever since. From 2001 until 2012 he worked for War Resisters' International (WRI) and today lives in Spain. Together, they use the example of Colombia to illustrate how international human rights mechanisms can be put to use in local cases, and in combination with other tactics, when campaigning for the right to conscientious objection.

On the international level, the right to Conscientious Objection (CO) has been on the political agenda of the UN General Assembly, the Commission on the Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities, the Human Rights Commission, and other UN institutions.1 In addition, the right is addressed by other international institutions, especially the inter-American and European systems.2 At the same time, different movements have implemented strategies to try to prioritise within states' agendas the recognition of the right to conscientious objection.

This is true of the Mennonite Church of Colombia, the Youth Network of Medellin, the Collective for Conscientious Objection, Conscientious Objectors' Collective Action (ACOOC), and the National Assembly of Conscientious Objectors. The work of these bodies focuses on the imposition of a culture of violence as a consequence of the more than 50 years of armed conflict in Colombia. Their work is concerned with victims of forced disappearances, sexual violence, forced displacement and people unlawfully recruited into the armed forces via military raids or 'press gangs'. It also addresses the lack of guarantees and protection of the right to freedom of conscience, doing so via training, awareness raising, accompaniment and advocacy strategies, alongside using international human rights protection frameworks.

This approach successfully combines work at a local level with the use of international mechanisms to achieve goals like the constitutional recognition of the right to conscientious objection and respect, protection and restoration of that right. It also preserves the social fabric in communities affected by violence and encourages the growth of peaceful conflict resolution skills and the use of alternative channels of influence.

In the next few years, this approach will have to confront at least 5 challenges. The first is to get all authorities to comply with the 2009 ruling of Colombia's Constitutional Court, which recognised the right to conscientious objection, as well as the 2014 ruling that established processes for the implementation of this right and obliged the recognition of conscientious objectors. The second challenge is that 'writ of injunction' – which is meant to be an exceptional legal measure, issued at the discretion of the given court – is currently used as the only available measure for guaranteeing the right to conscientious objection: this needs to change such that the right to conscientious objection is simply recognised by the authorities. The third challenge is to free objectors from the 'military card' – ordinarily obtained via the completion of military service – and the requirement to show this in order to get a job. The fourth challenge has to do with accommodating the nearly 800,000 young men who have decided they don't want be part of the army and evade or desert in order to avoid complying with the obligatory military service established by the Colombian Constitution, but who do not openly challenge the system of conscription nor take a political stand against it. Lastly, there is the challenge of getting the Armed Forces to respect the procedures established in Law 48 of 1993 (the Law on Recruitment), the rulings of the Constitutional Court, and international standards when defining young men's military status: currently they often do not respect these, meaning they ignore legal reasons for exemption to military service.

In the next few years, this approach will have to confront at least 5 challenges. The first is to get all authorities to comply with the 2009 ruling of Colombia's Constitutional Court, which recognised the right to conscientious objection, as well as the 2014 ruling that established processes for the implementation of this right and obliged the recognition of conscientious objectors. The second challenge is that 'writ of injunction' – which is meant to be an exceptional legal measure, issued at the discretion of the given court – is currently used as the only available measure for guaranteeing the right to conscientious objection: this needs to change such that the right to conscientious objection is simply recognised by the authorities. The third challenge is to free objectors from the 'military card' – ordinarily obtained via the completion of military service – and the requirement to show this in order to get a job. The fourth challenge has to do with accommodating the nearly 800,000 young men who have decided they don't want be part of the army and evade or desert in order to avoid complying with the obligatory military service established by the Colombian Constitution, but who do not openly challenge the system of conscription nor take a political stand against it. Lastly, there is the challenge of getting the Armed Forces to respect the procedures established in Law 48 of 1993 (the Law on Recruitment), the rulings of the Constitutional Court, and international standards when defining young men's military status: currently they often do not respect these, meaning they ignore legal reasons for exemption to military service.

Strategies

Colombian organisations have implemented diverse objectives and strategies to address the situation of violence in the country. There is a generalised sentiment amongst organisations that they don't want to contribute in any way to the war, whether in person or through the payment of taxes. On the contrary, they long for a society in which institutions and individuals reject the use of violence politically, philosophically, morally and ethically; a society that believes in and resorts to other mechanisms for the peaceful resolution of conflicts and is based on the respect, guarantee, and protection of human rights.

To achieve these goals, four strategies have been identified: the education of children and young people; awareness raising actions; judicial, political and psycho social accompaniment; and advocacy at the national level.

- Education of children and young peopl

Conscientious objector organisations and collectives have carried out educational programmes focusing on critical reflection about the armed conflict in Colombia, power, authoritarianism, the use of violence as a manifestation of power, the militarisation of society, and nonviolence. Information about conscientious objection has centred in particular on knowing the recruitment process and the procedure for exercising one's right to objection.

-

Awareness raising action

With the goal of disseminating information, efforts have turned to nonviolent direct actions which are informative and culturally engaging. These include advice sessions where young people and parents give advice about the recruitment process and illegal procedures during recruitment, as well as about how to access the right to conscientious objection. There are also concerts, public declarations, and street actions using contemporary dance, theatre, and other performance arts as tools for denunciating the status quo, reflection, and proposals for social transformation. An example worth highlighting is the creation of a spoof version of a free newspaper distributed in Colombia's main cities – in which the news published depicted an ideal Colombia, a Colombia that guaranteed the rights of disabled people, free of corruption, where it was possible to be a conscientious objector and not be required to show a military card to access fundamental rights such as work and education.

-

Judicial, political, and psychological accompaniment and advocacy at the national level

Since 2006, the Red Juvenil Medellín (Meddellin Youth Network) and ACOOC and its member organisations have, with help from War Resisters' Internatioanl (WRI) and the Quaker United Nations Office, adopted a plan to 'accompany' the cases of conscientious objectors, young people at risk of forced recruitment, and those who have already been recruited and want to get out. The plan consists of helping the objector to draft a document that expresses the political, judicial, ethical, moral, philosophical or humanitarian reasons motivating their objection. It is also meant to help objectors and their families confront situations arising from their exercise of their rights. The legal component, for its part, looks for legal mechanisms for requesting the right to conscientious objection, opposition to recruitment, and release from military service.

The declaration is entered in the WRI database, and the conscientious objector is issued with a card that identifies them as such.

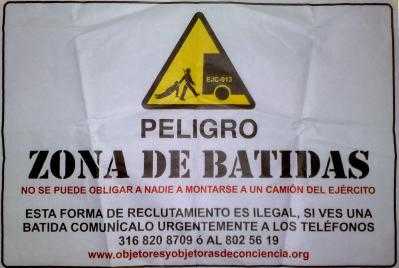

The declaration or petition is distributed, as appropriate, to the Office of Recruitment, the Military District, the Office of the Ombudsman, the municipal or district Human Rights Advocate, the Colombian office of the United Nations High Commission for Human Rights, the Vice Presidency of the Republic, and the Ministry of Defence. Alongside the declaration is a letter of support from WRI and the organisation charged with accompanying the case in the hope of a positive response. Up until now, the institutions in charge of recruiting have highlighted that the right to objection does not have any legislation to support it, whereas obligatory military service is supported by the Military Recruitment Law (Law 48 of 1993). The institutions in charge of defending citizens' rights, meanwhile, have insisted that their job is to pass the declaration or petition onto the 'competent authority', as they don't have the legal authority to make final decisions on the matter. At the same time, recruitment by press gangs has become more visible.

To confront these responses, local organisations have activated the National and International Accompaniment Network formed by WRI, the Quakers, Conscience and Peace Tax International, Fellowship of Reconciliation, CIVIS, the Objectors Movement of Spain (MOC), the Objectors Movement of France, and others. These organisations deliver letters to national institutions demanding they respect young people's rights and comply with their legal duties towards them.

From when the strategy was implemented to now, ACOOC alone has accompanied the declarations of approximately 190 objectors, of whom 7 are women, one is a transgender man, and the remaining 182 are cis men of recruitment age (men who were called boys from when they were born). Thanks to this accompaniment, none of these declared objectors have been recruited and many illegally recruited young people have been released from military service. It would seem that the growing number of declarations speaks to an ever bigger group of young people rejecting enlistment into military service.

-

Advocacy in the state human rights institutions

Parallel to these declarations and political, legal, and psycho-social accompaniment work, Colombia's objector organisations have carried out advocacy and lobbying actions on a national level that have affected the perspective and practices of the authorities regarding conscientious objectors, recruitment via press gangs, and the requirements of the military card.

Collectives in support of conscientious objection and international organisations have met with national institutions to educate and pressure them to guarantee the right to conscientious objection. This work has slowly led to those institutions taking positions in favour of such a right: it has achieved the support of the Human Rights Office of Medellin (Personería de Medellín) and the Office of the Ombudsman (Defensoría del Pueblo), for example. Both institutions are familiar with the cases and have interceded in favour of conscientious objectors or young people recruited by force, including those recruited before the ruling of 2009.

They have also attended seminars, talks and meetings in order to create dialogue around the guarantee of the right, the advantages of applying the framework of legal norms regarding conscientious objection including international standards which exist, and the consequences of failing to do so.

-

The use of international human rights frameworks by conscientious objector organisations in Colombia

For many years, the legal route to demanding the right to conscientious objection in Colombia was closed. The Constitutional Court ruled on various occasions against the right (T-409/92, C-511/94, T-363/95).1 To advance recognition of the right, the use of international human rights mechanisms and institutions was essential. A first step was the case of objector Luis Gabriel Caldas León (Case 11.596) before the inter-American Commission on Human Rights in 1995, though this was unfortunately shelved in 2010 for lack of information.2

Since 2000, efforts have focused on the diverse mechanisms and institutions of the United Nations human rights system. Conscientious objector organisations have established contact with the Colombian office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, alerting the office to violations of conscientious objectors' rights and young people's subjection to irregular recruitment processes in the form of raids or 'press gangs'. In 2010, the Office issued a report publicly criticising such practices for the first time and recommending an end to them as soon as possible.3

The inclusion of these two themes in the Office's reports has much to do with achievements in the international human rights arena. The global strategy – especially after the explicit recognition of the right to conscientious objection by the Human Rights Committee in its ruling on the case of Yeo-Bum Yoon and Mr Myung-Jin Choi versus South Korea in January 2007 – is to obtain concrete declarations on cases or situations in Colombia through various human rights mechanisms, in order to increase the pressure on human rights institutions as well as courts within the country, whose primary references would otherwise be the negative rulings of the Constitutional Court.

The focus has been on the use of three particular mechanisms:

-

The working group on arbitrary detentions: In 2007, WRI submitted three individual cases of illegally recruited young people: two cases of conscientious objectors, and one young person who had been recruited by press gang. The result of the case was very successful, with two important aspects:

-

The working group strongly criticised the practice of raids, saying that 'raids, incursions, or round ups with the goal of detaining young people in public spaces who can't prove their military status, don't have any legal basis or justification'. Consequently, such recruitment and consequent deprivation of liberty in a barracks was declared 'arbitrary detention'.

-

In addition, the working group clearly clearly stated that 'the detention of said people who have explicitly declared themselves to be conscientious objectors does not have judicial substance or legal basis, and their incorporation into the army against their will is a clear violation of their acknowledgement of conscience.'4

The working group also produced a similar statement during and after their visit to Colombia in October 2008.5

The Human Rights Committee: Conscientious objection was included for the first time in the 2004 Human Rights Committee's report in its recommendations and final observations. They recommended that 'The State Party should guarantee that conscientious objectors can opt for alternative service whose duration does not have punitive effects.6 On this basis, Colombian conscientious objectors' organisations and their international allies – mainly WRI and Conscience and Peace Tax International – worked to raise awareness and inform the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights in Geneva as well as the Human Rights Committee and its members. In the next review, various alternative reports on military recruitment and conscientious objection were submitted.7 As a result, the Committee recommended that Colombia 'should, without delay, adopt legislation that recognises and regulates conscientious objection (…) and reform the use of raids'.8

-

The Universal Periodic Review: Conscientious objection as well as raids were included in the information summary compiled by the Office of the High Commissioner. During the Universal Periodic Review in December 2008, Slovenia submitted a recommendation that Colombia recognise the right to conscientious objection in law and practice, and ensure that recruitment methods permit for this. However, Colombia didn't accept this recommendation (A/HRC/10/82/Add.1, 13 January 2009). Even though both topics were briefly mentioned in the report from the Office of the High Commissioner (A /HRC/WG.6/16/COL/3, 7 February 2013), during the second cycle of the Universal Periodic Review (16th session) there was no recommendation related to conscientious objection.9

In addition to these three mechanisms, specific cases have been communicated to the Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief. The declarations made by the institutions of the United Nations human rights system have created a strong shift in judicial opinion, as can be observed in the 2009 Constitutional Court ruling C-728 recognising conscientious objection as a fundamental right.

Increase the pressure: the unconstitutionality ruling

With the unfolding of international law and the declarations of international institutions regarding the lack of recognition for the right to conscientious objection in Colombia, space has opened on a national level for a new judicial initiative.

In May of 2009, Gina Cabarcas, Antonio Barreto and Daniel Bonilla submitted a claim of unconstitutionality before the Colombian Constitutional Court in which they argued that the lack of provision for the right to conscientious objection in the Military Recruitment Law is a violation of the Colombian Constitution. In this process, the Ministry of Defence testified against the petition. Testifying in favour there were law professors, Dejusticia (the Centre for Law, Justice and Society Studies), and the Colombian Commission of Judges, among others. It is also important to note that the Attorney General intervened with his own position paper, and the Medellin Human Rights Office supported the position of the Colombian Commission of Judges in favour of the unconstitutionality claim – demonstrating civil society's efforts to move public opinion towards supporting the right to conscientious objection.10

Even though the Constitutional Court formally rejected the claim of unconstitutionality under the reasoning that conscientious objection is not an exemption from Obligatory Military Service, the Court argued that as part of freedom of conscience there should be specific legislation regulating the right and ordered Colombian Congress to enact a law on the matter. In addition, the Court provided some key points for understanding and demanding the right:

-

The Court highlighted that despite the lack of legislation governing the right to conscientious objection, this right has immediate effect and protection can be provided via a 'writ for protection' (court injunction), in case it is not recognised (see section 5.2.6.5 of the court ruling).

-

The Court clarified that conscientious objection can be based upon religious, ethical, moral or philosophical beliefs, and insisted that it cannot be limited to religious reasons (paragraph 5.2.6.4).

-

The beliefs that give rise to the conscientious objection should be profound, sincere and fixed. As a result, the Court stated that all conscientious objectors would have to demonstrate the external manifestations of their convictions and beliefs, in order to prove that military service would force them to act against their conscience (paragraph 5.2.6.2).

-

Since then: lack of recognition of conscientious objection in practice

Five years since the Constitutional Court published Ruling C-728, the legislature has not complied with its duty to protect the constitutional right to conscientious objection. Between 2009 and 2014 there have been various proposed laws (66/2010, 135/2010) which have not been approved.11 The last attempt was a bill proposed in 2012, which was shelved in 2013 at the end of the legislative term.

During the legislative sessions, national and international organisations recommended that the law not restrict the right to conscientious objection, for example only to religious objections. They described a clear and smooth procedure, and envisaged at least two levels of appeal to resolve objectors' cases: a social service which does not discriminate against the objector, and a credential giving the same benefits as the military card. Relatedly, they worked on other matters, like Law 1738 of 2014, which eliminates the obligation to have a military card in order to obtain a professional degree.

Despite the failure of the legislation, a small group of young people have had their conscientious objection recognised on non-religious grounds thanks to the Supreme Court of Justice's penal appeals court having overturned a ruling issued by the criminal court of the Bogota High Court, which had denied that there was any infringement of the right to conscientious objection by the Ministry of Defence, the National Recruitment Office or Military District Number 59.12

In addition to the cases that have been successful however, there are many young people whose right to conscientious objection has not been recognised and many more who were and are illegally recruited by the authorities. The Ombudsman's Office recently published the report Military Service in Colombia: Joining, recruitment and conscientious objection,13 which includes a survey of the right to objection. The report documents the problems related to the right to objection: 'Given that conscientious objection is not recognised as a reason for exemption, the military authorities don't fully resolve the requests lodged by those who wish to be recognised as conscientious objectors.'

Practical problems with the protection of the right, and the problems arising from raids — despite these being classified as illegal by ruling C-879/11 of the Constitutional Court — led to a new ruling by the Court on the two matters in 2014, in which it described the right to conscientious objection right in more detail:

-

the right to conscientious objection does exist, even though no law exists on conscientious objection in Colombia;

-

the right is recognised and protected at all times: before, during and after military service;

-

the armed forces have to respond to a request for the right within a period of 15 days;

-

they also have an obligation to inform young people regarding their right to conscientious objection;

In fact, because of the legislature's inaction, the Constitutional Court is dictating the terms of a conscientious objection law.

Even though the Court may contribute positively to the development of the right, the gap between theory and practice in the country continues to be stark. Even in 1997, the Human Rights Committee observed 'with concern the large discrepancy between the legal framework and the reality in relation to human rights' 14. Ten years later, this concern remains relevant. So long after the recognition of conscientious objection by the Constitutional Court in 2009 as well as its ruling on the illegality of raids in 2001 (C-879/11), recruitment practices have changed little. There are serious doubts about whether the new ruling from the Constitutional Court will have a broader impact.

Conclusions

The achievements of the conscientious objector collectives in Colombia in the last 15 years are impressive. We are convinced that these achievements have only been possible though the use of a combination of strategies, including national and international legal means, as well as awareness raising strategies and young people mobilising for their rights.

Social mobilisation — especially of young conscientious objectors — was necessary in order to put the issue of massive human rights violations on the agenda. This mobilisation and advocacy work have made it possible for some state human rights institutions to finally support the claim of unconstitutionality against the lack of provision for the right to conscientious objection, support that we consider important to the success of said claim.

Furthermore, advances in international law and specific declarations from international bodies have increased the pressure on the Colombian judicial system regarding the claim of unconstitutionality. Obviously we don't know the content of the debates had by the Constitutional Court judges, but we believe the combination of the two factors — social mobilisation and international institutions — to have been very important.

We also think it is strategically important to widen the cracks in the system and not consider 'the state' to be a monolithic system. The contradictions between different administrations within the same State have been made visible during the unconstitutionality case, for example in the intervention of the Ministry of Defence against the right to objection while the Attorney General and the Human Rights Office of Medellin were in favour.

Even though the successes are impressive, there is still much to do in order to achieve the political and social goal of freedom of conscience, namely societal demilitarisation and nonviolence. Though the protection of human rights — and in this case the right to conscientious objection — can only widen and protect the social space for young people, social movements, and their struggles, they don't in themselves change society. Additionally, the focus on the right to objection— by definition strictly related to obligatory military service — favours a focus on young men, even though militarism and violence also have a strong impact on the lives of women, and in Colombia women are important actors in the movement for conscientious objection.

Every country is different and lives within its own particular context. However, the example of Colombia can serve as inspiration for other struggles — adapted to the particular context.

Translated from Spanish by Denise Drake and Ian MacDonald.

Published in War Resisters' International: Conscientious Objection: A Practical Companion for Movements and online at https://wri-irg.org/en/cobook-online/impact-international-mechanisms-Colombia.

1. cf. CPTI 2005, Military Recruitment and Conscientious Objection: a thematic global survey [online], CPTI.ws, <https://www.cpti.ws/cpti_docs/brett/intro.html>, accessed 2nd July 2015.

2. cf. WRI 2013, Guide to the International Human Rights System for Conscientious Objectors [online] <https://co-guide.info/>, accessed 2nd July 2015.

3. These cases may be searched online at <https://www.corteconstitucional.gov.co/relatoria/>, accessed 2nd July 2015.

4. Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) 2010, Report 137/10, 23 October 2010 [online], <www.cidh.oas.org/annualrep/2010sp/125.COAR11596ES.doc>, accessed 2nd July 2015.

5. Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) in Colombia, 2010, Report of the United Nations Hight Commissioner for Human Rights on the human rights situation in Colombia, 2009, 10 March 2010, <http://www.hchr.org.co/documentoseinformes/informes/altocomisionado/informes.php3?cod=13&cat=11 >, ; OHCHR 2011, Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the human rights situation in Colombia, 2010, 24 February 2011, <https://www.hchr.org.codocumentoseinformes/informes/altocomisionado/informes.php3?cod=14&cat=11>, accessed 2nd July 2015.

6. UNHRC 2009, Opinions Adopted by the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention, <http://daccess-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G09/107/13/PDF/G0910713.pdf?OpenElement>, Opinion 8/2008 (Colombia), accessed 2nd July 2015.

7. Working Group on Arbitrary Detentions (WGAD) 2009, Report of the working group on arbitrary detention. Addendum: Colombia Mission [online], A/HRC/10/21/Add.3, 16th February 2009, <http://daccess-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G09/107/13/PDF/G0910713.pdf?OpenElement>, accessed 2nd July 2015.

8. UNHCHR 2004, Concluding Observations of the Human Rights Committee : Colombia (05/26/24), CCPR/CO/COL (Concluding Observations/ Comments) [online], <http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/AboutUs/annualreport2004.pdf>, para 17, accessed 2nd July 2015.

9. War Resisters' International 2009, 'Military Recruitment and Conscientious Objection in Colombia'. Report to the Human Rights Council, 97th Session, August 2009, <https://wri-irg.org/es/story/2009/reclutamiento-militar-y-objecion-de-conciencia-en-colombia?language=es>, accessed 2nd July 2015.

10. UNHRC 2010, Consideration of Reports Submitted by States Parties under Article 40 of the Covenant: Concluding Observations of the Human Rights Committee: Colombia [online], <http://www.univie.ac.at/bimtor/dateien/colombia_ccpr_2010_concob.pdf>, accessed 2nd July 2015.

11. The archives of the UNHR Periodic Reviews may be accessed at <http://www.ohchr.org/EN/PublicationsResources/Pages/OHCHRArchives.aspx>.

12. The details of this case may be accessed at <https://www.corteconstitucional.gov.co/relatoria/2009/C-728-09.htm>.

13. The archive of Colombian law may be accessed at <https://www.archivogeneral.gov.co/leyes>.

14. See for example Constitutional Court sentence T-455, 7th July 2014 <https://www.corteconstitucional.gov.co/relatoria/2014/T-455-14.htm>, accessed 16th July 2015.

- Log in to post comments